Over the last one and a half years, direct income transfer schemes have increasingly emerged as alternatives to farm loan waivers in the agriculture sector. While the macro-level impact of these schemes on farmers welfare is yet to be seen, direct income transfers seem to have emerged as an effective tool to make the agriculture sector more conducive to the use of data for policy formulation and scheme and service delivery. The processes undertaken for beneficiary identification and last mile delivery of assistance as part of these schemes have led to strengthening of numerous datasets and technological systems within the agriculture ecosystem. The experience of Government of Odisha is illustrative in this context.

In December 2018, Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment (DA&FE), Government of Odisha launched a direct income transfer scheme called ‘KALIA’ - Krushak Assistance for Livelihood and Income Augmentation, for small/marginal farmers and landless agricultural labourers of the state. The state embarked on an unprecedented journey by covering landless labourers and tenant farmers under the ambit of this scheme. This was the first time any state or central government had included this section of the agriculture workforce in such a financial assistance scheme.

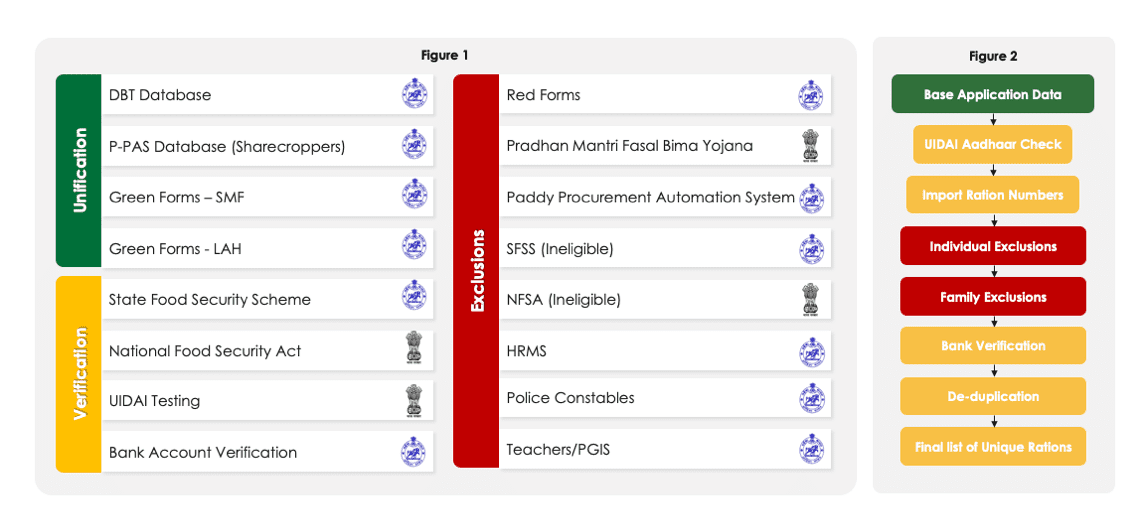

DA&FE, supported by Samagra, adopted a comprehensive beneficiary identification framework (as shown in Figure 1), with a threefold approach of Unification, Verification and Exclusion. It analyzed, organized and triangulated more than 20 databases to conceptualize a data-backed beneficiary identification algorithm, (as shown in Figure 2). In cases where the state did not have the requisite database in usable form, such as the list of farmers registered under the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) scheme, it was procured from Government of India or other national agencies.

What is the Unification-Verification-Exclusion framework

- Unification – As a first step, DA&FE’s existing Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) database of 21.7 lakh farmers and the state’s list of 1.05 lakh sharecroppers under the Paddy Procurement Automation System (P-PAS) were utilized. In addition to this base list, in a period of one month, approximately 1 crore applications were received under the scheme. Applications from all these sources were unified to create a base applicant list of approximately 1.2 crore.

- Verification – The entire base list of applications was run through multiple checks including Aadhaar authentication through UIDAI and bank verification through State Level Banker’s Committee (SLBC) to eliminate the possibility of any ghost or duplicate applications in the final beneficiary list. Additionally, since KALIA is a farm family scheme, ration numbers under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) and State Food Security Scheme (SFSS) were used to identify members belonging to the same family.

- Exclusions – On the basis of eligibility criteria defined under the scheme, the list of verified applications were run through various databases to flag and exclude ineligible applications.

To prevent any false inclusions i.e. inclusion of ineligible applications in the final beneficiary list, a three-tier field verification mechanism encompassing verification at gram panchayat, block and district levels was undertaken. Thereafter, to identify and resolve false exclusions i.e. exclusion of eligible applications, an online grievance redressal mechanism has been opened for all the applicants.

The result? After extensive verification, in a span of 5 months, 50 lakh beneficiaries were identified and assisted under the scheme. Moreover, 70% of the beneficiaries identified under this scheme are not present in any other substantial farmer list held by either the state or central government. Thus, through the KALIA scheme, the state government has not only assisted 50 lakh farm families, but has also been able to create a verified list of farmers, including landless agricultural labourers, as a long-term asset covering 77% of the estimated 65 lakh farm families in the state.

Similarly, Government of India and Government of Telangana through their PM-KISAN and Rythu Bandhu schemes have been able to create verified farmers’ databases of 8 crores and 58 lakhs respectively.

These databases of farmers have the potential to not just transform and streamline scheme and service delivery but also enable other use cases such as customized agro-advisory dissemination, farmer-level input requirement assessment and fraud detection among others. Most of the governments have already recognized this potential, and have been taking active steps in this direction. While Government of India is working on creating a federated farmers’ database for the country, many state governments, including Odisha, have also started supplementing by working on creating such a unified database of farmers. Government of Odisha, in fact, has taken a step further and has started implementing use cases with this database. In collaboration with Precision Agriculture for Development’s (PAD) ‘Ama Krushi’ initiave, Government of Odisha is disseminating customized agro-advisory to its verified list of farmers. And this is just the beginning!

Therefore, most direct income transfer schemes, even if they are designed differently, hold the potential for accruing multiple long-term benefits, including the following -

- Generate visibility into the current levels of data and information available

- Accelerate the creation and strengthening of a farmer-level database

- Lead to capacity building and a mindset shift of government officers involved in the process with respect to data creation and data usage

Thus, while direct income transfers are propped up as a sound policy choice for several economic reasons, if implemented well, they hold the potential to transform the way the entire agriculture sector functions.